By Susan Pinker

https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-happy-can-a-windfall-make-you-11669240314

How would you feel if an anonymous benefactor gave you $10,000 to spend within the next three months, no strings attached? Would suddenly being flush with cash fill you with joy?

That question sparked a remarkable study published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Lead author Elizabeth Dunn, a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia, along with her doctoral student Ryan Dwyer, knew from prior research that there tends to be a correlation between receiving a sum of money and being happier. But those studies didn’t untangle the direction of causation—whether happier people made more money, or whether money made people happy.

The opportunity to dig deeper fell in their laps in 2020, when two anonymous donors offered to give Chris Anderson, the CEO and chief curator of TED, $2 million to distribute to worthy individuals around the world. Mr. Anderson then contacted Prof. Dunn. Might she be interested in studying the impact of these gifts? “Hell, yeah,” she answered.

After weeding out those whose lives might be endangered by a sudden influx of cash, the study ended up with 300 participants. Two hundred were randomly chosen to receive $10,000 via PayPal. The remaining 100 respondents served as the control group. All participants had completed a baseline survey about their psychological well-being and annual earnings at the beginning of the experiment, then completed follow-up surveys one, two, three and six months after the cash was distributed. Members of the control group received $25 each time they filled out a survey.

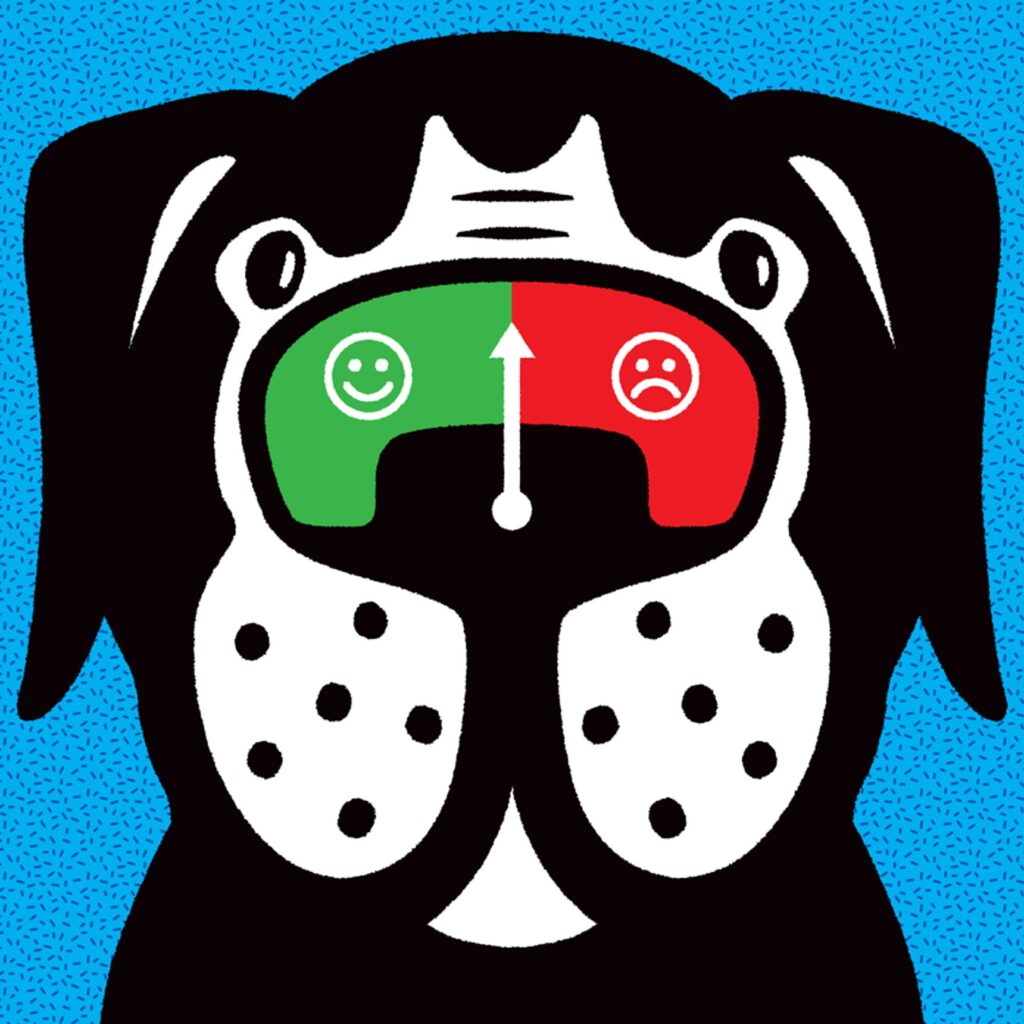

The researchers found that, as might be expected, a big windfall made people happier than the drip-drip-drip of repeated $25 gifts. But the money didn’t have the same effect on everyone. “The gains were greatest for recipients who had the least,” the paper found. People in lower-income countries who received $10,000 gained three times more happiness, based on the self-reported surveys, than those in higher-income countries. For recipients whose annual income was $100,000 or above, the gain in happiness was diminished.

Comparing participants in the same country, those who made $10,000 a year gained twice as much happiness from the windfall as those making $100,000 a year. “This is consistent with a mountain of research showing that the more we have of something, the less we feel about increases. Those with lower income get a better boost,” said Prof. Dunn.

In 2021, four billion people worldwide lived on less than $6.70 a day. The new study suggests that if any of them got a cash gift with no strings attached, a smile would likely appear on their face. Perhaps such giving should become a Thanksgiving tradition, along with turkey and football. “My fondest wish is that people will emulate what this couple did,” said Prof. Dunn. For people who have money to spare, giving it away creates “more happiness than if you kept it for yourselves.”