Dogs Can Sniff Out Human Stress

By Susan Pinker

https://www.wsj.com/articles/dogs-can-sniff-out-human-stress-11666274196

Dogs are champion sniffers, equipped with 100 to 300 million olfactory receptors in their noses—compared with a mere 6 million in our own—and an olfactory cortex 40 times as large as ours. They can be trained to detect disease in human beings, including cancer cells, a latent epileptic seizure, or a Covid infection, just by sniffing—no blood samples, biopsies, MRIs, antigen or PCR tests required.

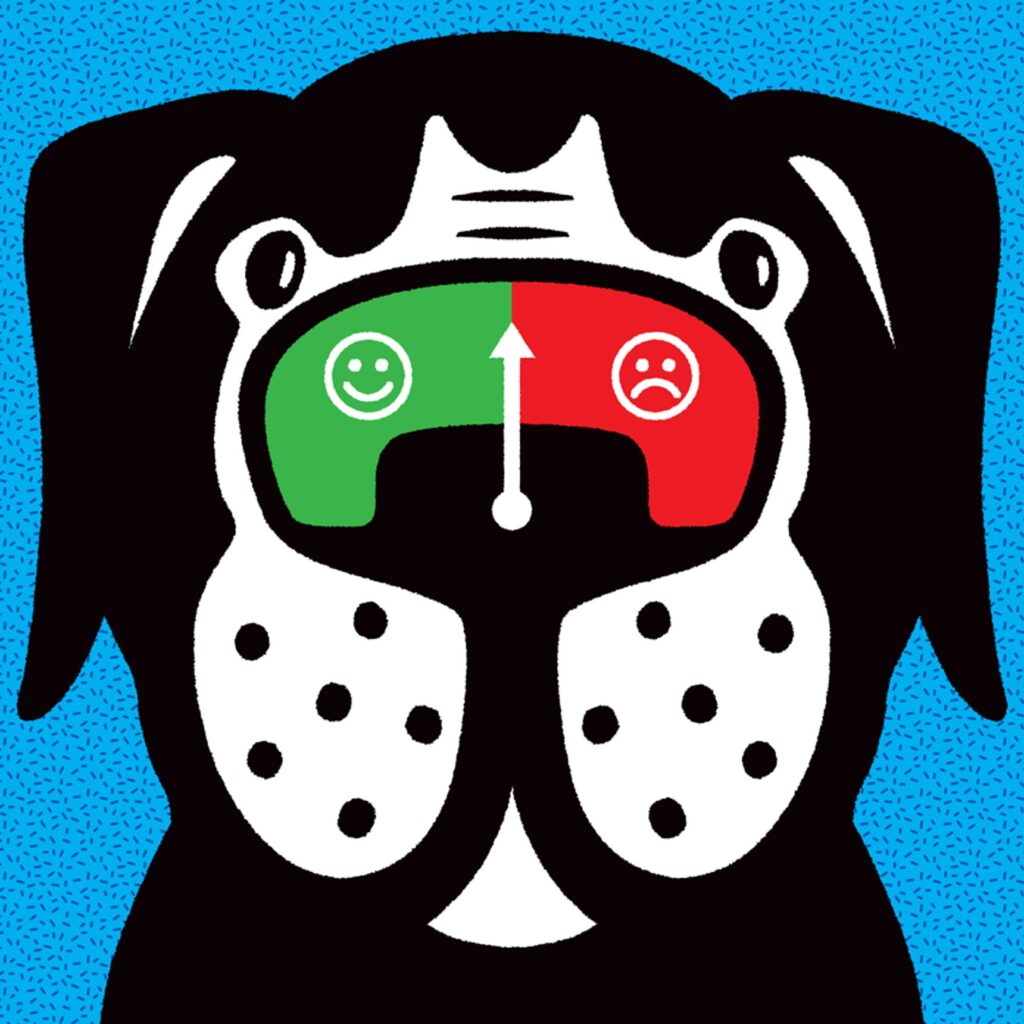

Can dogs smell something as ineffable as psychological distress? Mood disorders have surged since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the demand for emotional support dogs has followed suit, with customers paying anywhere from $15,000 to $50,000 for a dog trained to respond right before a panic attack, or when the owner’s PTSD or addictive cravings bloom. Until recently, evidence that dogs can sniff out our psychological states remained anecdotal. “The assumption that dogs can identify a person’s psychological state is the reason why we have service dogs for PTSD, anxiety disorders and depression,” says Clara Wilson, a researcher at the Animal Behaviour Centre at Queens University Belfast. “It seems so obvious that no one has tested the idea empirically. Until now.”

In a study published in September in the journal PLoS One, Ms. Wilson and colleagues tested whether dogs can read and respond to our emotional states, without the benefit of facial expression, tone of voice, or social context. The researchers trained four dogs to detect and react to the smell of human stress, depending on their sense of smell alone to distinguish between a person’s baseline scent and the unique cocktail of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in their sweat and breath when they’re feeling stressed out.

Using tasty rewards, the researchers trained the dogs to distinguish between three gauze samples. One was neutral, containing no human scent. The second had been breathed on and then wiped across the back of the neck of one of 36 human participants at a moment when they felt completely relaxed. The third set of sweat-and-breath samples was taken before and after the participant completed an arithmetic task under time pressure. The humans’ heart rate and blood pressure were monitored, to confirm that the smell of the gauze was indeed a sign of stress.

The goal was to teach the dog to pick out the “stress” sample from a set of three swatches and indicate it by sitting up in front of that sample, alert and attentive. To avoid giving the dog any inadvertent visual or social cues, each swatch was presented behind a grill, so it couldn’t be seen or touched, and no humans were present during the test. If the dog could pick out the stress sample from the distractors, he or she was rewarded with something good to eat.

The results offered overwhelming confirmation that dogs can smell psychological states as well as physical ones. On average, the four dogs picked out the stress sample 94% of the time, with individual dogs ranging between 90% and 97% accuracy. “There’s a smell to stress,” Ms. Wilson concludes. “If we can add it to the dog’s repertoire, we can use it to identify anxiety and panic attacks before they occur.”