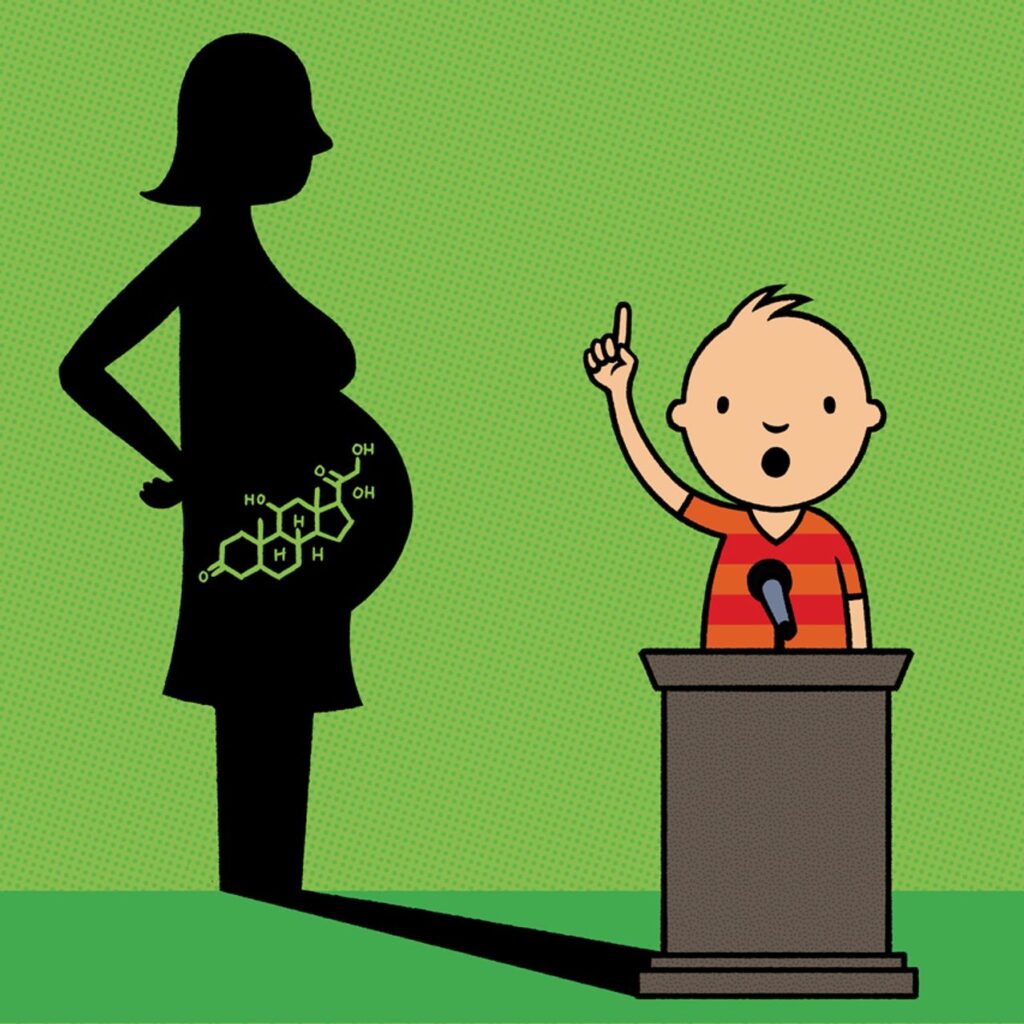

Prenatal Stress May Make Children More Verbal

By Susan Pinker

https://www.wsj.com/articles/prenatal-stress-may-make-children-more-verbal-3b468a0f

Cortisol floods your bloodstream every time you feel stressed out. This biochemical messenger heralds an incipient attack—real or imagined—and instructs your body to gird itself for danger. But the hormone can have contradictory effects; it plays the role of hero or antihero, depending on the context. Doctors prescribe it to reduce inflammation and tamp down the immune system when it goes haywire, for example. But cortisol released during periods of extended psychological stress can also damage your heart and kickstart a major depression.

“Cortisol has a bad reputation,” says Anja Fenger Dreyer, a physician and a research fellow at the University of Southern Denmark. Studies have repeatedly linked high levels of stress-related cortisol to preterm births, extremely small newborns and postpartum depression in mothers. At the same time, Dr. Dreyer explains, “It increases during [a healthy] pregnancy and is good for fetal development. In preemies [cortisol] is used to help mature the organs, like the lungs, brain and heart.”

Dr. Dreyer is a lead co-author of a remarkable new study, presented in May at the annual European Congress of Endocrinology, which adds yet another dimension to the cortisol paradox. Researchers found that pregnant mothers who were anxious during their last trimester, and thus secreted lots of cortisol, gave birth to babies who became excellent listeners and talkers as toddlers. The more cortisol circulating in the mother’s bloodstream late in pregnancy, the more advanced the toddler’s understanding of words, and the more words they said between one and three years of age.

The researchers drew their data from the Odense Child Cohort study, which began with 2,500 healthy, pregnant women living in the Danish city of Odense from 2010 to 2012. After dropouts, 1,093 children remained in the study. To study the developmental effects of prenatal cortisol, blood samples were collected from the mothers during pregnancy. Researchers monitored the children in utero and examined them every two years after they were born, as well as taking samples of their blood and hair.

When the children were between the ages of 1 and 3, every three months the parents completed a standardized language survey, the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory, which required them to tick off which words their toddlers understood or said from a list. According to this new study, the more cortisol produced by a pregnant mother during her third trimester, the more advanced her toddler’s language abilities.

The findings suggest that prenatal cortisol may be a bigger player in human development than previously thought. But there’s still much to untangle, including the role of sex differences. Intriguingly, the researchers found that boys whose pregnant mothers secreted more last-trimester cortisol produced more words, while girls exposed to greater cortisol understood more words. This may be connected to the fact that pregnant women carrying girls generally secrete more cortisol than pregnant women carrying boys. On average, girls’ language skills tend to be more advanced than boys’ in all populations, and cortisol may give us a clue as to why that is.